Managing by algorithm

Workforce morale and customer satisfaction at risk

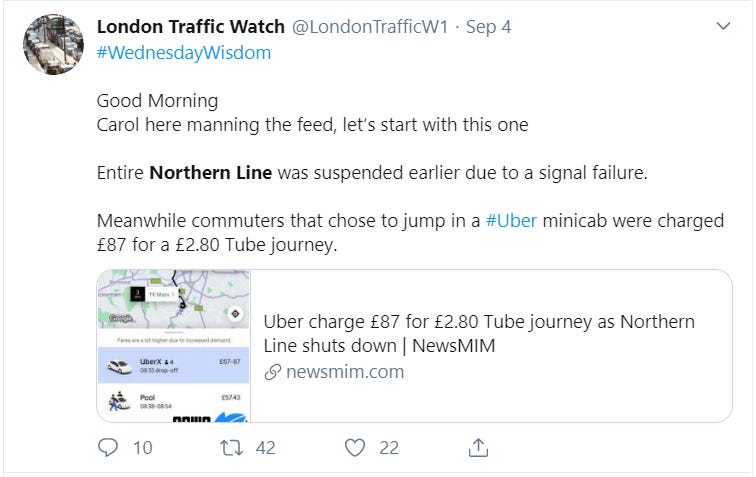

Picture this common scenario for London commuters: it’s the first day back to school after the summer holidays, it’s raining, it’s the morning rush hour and the Northern line isn’t working. Seasoned commuters will know that buses are an option, but it will be a tight squeeze to get into one. Disruptive seasoned commuters will know that we now we have a different option, we can get an Uber to the nearest alternative station! This exact scenario played out a few weeks ago and there was a mini-outrage on social media when a 10-minute journey ended up costing over £80 pounds.

As expected, social media opinions ranged from anger at how Uber benefits from people’s misery to acceptance that this is capitalism in action and Uber is just reflecting the real ‘value’ of a 10-minute journey evaluated by supply and demand and accelerated by algorithms designed to optimise their outcomes.

I looked at this from a different perspective; to me this is a perfect example of the new challenges emerging from the practice of algorithmic management. I was curious to find out how the drivers would justify the price. Side with the passengers feeling ripped-off? Dive deep into the intricacies of surge pricing? Shrug their shoulders and blame the system?

“Algorithmic management is not an example of a technology-supported management practice; in fact, it constitutes a totally different managerial logic. Specifically, algorithmic management has the unique ability to track worker behaviour, constantly evaluate performance with rewards and penalties and automatically implement decisions. Algorithmic management provides the feeling of working with a “system” rather than humans and is characterised by lower transparency.1”

The feeling of being managed by some obscure, impregnable system has generated some interesting coping mechanisms by the growing number of people who work in these environments. I was fascinated by a report showing how a group of Uber and Lyft drivers working outside an airport in Washington would coordinate to switch off their apps to create an artificial absence of cars prompting the systems in both Uber and Lyft to trigger a price surge. An original way to regain control or just plain old cheating?

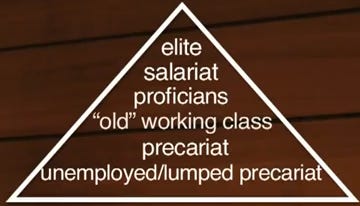

The impact of the gig economy on the workforce is not a new phenomenon, some social commentators have described a new emerging class of the ‘precariat’ which describes a growing socio-political group who share an increasingly precarious lack of job security. Algorithmic management has not created the precariat but is certainly defining the framework for managing this dispersed workforce.

Even though the most dramatic examples involve people working in the gig economy, the experience of being managed by an algorithm is becoming more common and is something which is manifesting itself in housing. Rent officers in many organisations regularly follow algorithm-based logic to decide who to call and chase for payment. Repairs operatives look at their devices to tell them which job to handle next and a transactional satisfaction survey is sent for customers to complete as soon as they leave. With the introduction of machine learning products embedded in Outlook which give users ‘nudges’ on how to become more productive, which emails need urgent action and suggestions to prevent spending too much time on meetings, this trend not only affects gig economy workers but is becoming more widespread and will continue to grow.

There is a fascinating study about the impact algorithmic management has on gig economy workers and I think it provides valuable insight for housing providers. The three most common complaints from workers managed by algorithms are:

Constant surveillance - Staff feel the work is too prescriptive with every task decided by the algorithm and the threat of potential punishment for non-compliance. There’s also the personalised feedback loop from customers in the form of which adds to the feeling of lack of freedom

Lack of transparency - As per the example of the price surge in London, staff feel they need to operate under the instructions of an opaque system which manipulates their activities towards goals which are totally out of their control

Loneliness - Perhaps in common with home workers, staff feel isolated without colleagues to engage with or supervisors to build a relationship with.

All of this is triggering online activism with communities of gig economy workers sharing their experiences away from their employers. In some recent examples, fledgling trade unions are being formed to represent this growing workforce. Mark Graham, one of the key thinkers in the domain of the gig economy, has suggested the need for a transnational digital workers union.

Even if we don’t recognise all these traits in our workforce yet, we need to keep learning from the experience of other sectors and avoid some of the excesses described here. Practising openness and transparency, enabling human contact for dispersed teams, building trust around the goals of the organisation and ensuring that algorithms are optimising their output in line with the company’s goals, are all steps which will go a long way to preventing some of the unintended consequences of algorithmic management.

Keeping an eye on these new ways of managing people by algorithm is not only important from an HR perspective but it may have a deep impact in terms of customer satisfaction. The reason why the housing sector is looking to digital transformation and innovation is ultimately to improve the service it provides to its customers. The learning from the more extreme examples of the gig economy show us that a workforce which is experiencing unmitigated algorithmic management will be unable to provide an excellent customer service. This poses a significant challenge now when tenants expect more from landlords and are finding their voice to state their rightful demands to be listened.

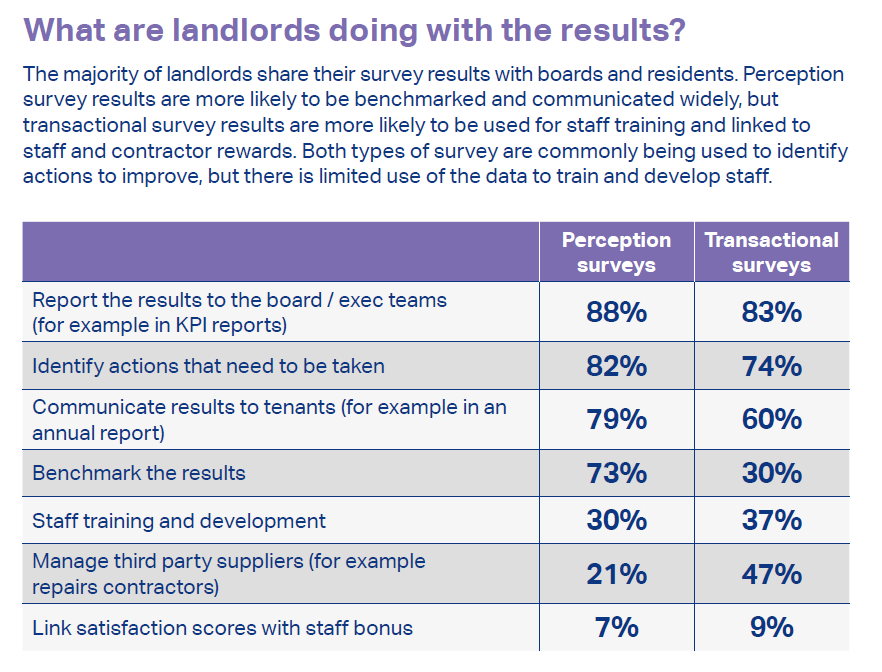

At HouseMark we have been leading the collection of customer satisfaction data since 2011 when we launched the STAR framework. This year we have been carrying out a review of STAR to ensure we maintain a modern approach to capturing customer satisfaction data. We’ve had significant traction with over 250 landlords and over 7,000 residents participating in the review.

It is very interesting to see the prevalence of transactional satisfaction measures used in the sector. Landlords find these a highly effective way to manage third party contractors and define staff rewards. This is not in itself a problem but the lessons from the gig economy should help define a safe path where the combination of algorithmic management and the use of immediate feedback loops doesn’t cause unintended consequences such as low staff morale which will ultimately impact on satisfaction scores.

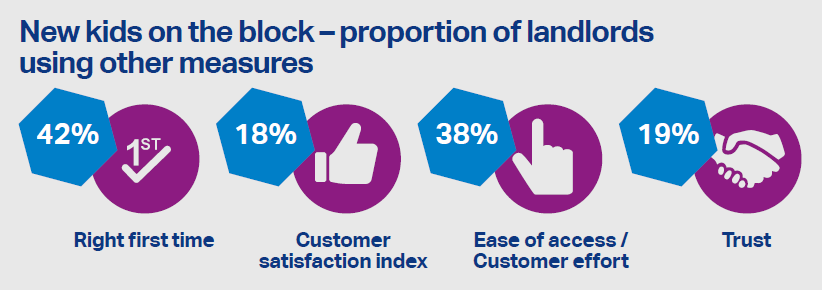

Another interesting insight from the review is the use of satisfaction measures which evaluate ease of use and trust. This is another area where landlords should monitor the impact of some of the algorithmic management challenges particularly when measuring trust. Some of the providers of mass-scale services supported by the gig economy workforce such as Uber or Amazon may accept a low trust score because they know customers will be willing to sacrifice trust for convenience. This is not the case in social housing where the product is the home and trust is a precious commodity. If staff feel they are managed by an impersonal system which they don’t understand, it is very unlikely they will be able to engender the kind of trust in customers needed to successfully deliver the service.

When the new STAR framework is released in December 2019, the sector will have a new mechanism to capture satisfaction and providers will be able to ensure some of the inevitable changes brought about by technology and algorithmic management don’t create unintended consequences which impact their satisfaction scores due to low staff morale.

So the next time I get a nudge from Outlook telling me to respond to an email or to leave more time aside for collaboration, I will remember that for every fantastic new invention there is a potential unintended consequence and it is the job of the disruptive innovator to keep looking for them before they materialise and design strategies for safe adoption.

This article was published in the fourth issue of the DIN BulletinTaken from a recent report by Mareike Möhlmann and Lior Zalmanson on Uber drivers and their views on being managed by algorithm