The unaware home

Terms and conditions apply at the bottom of Maslow's pyramid

I’ve been reading a very interesting book over the last few weeks. ‘The age of surveillance capitalism’ by Shoshana Zuboff is a critical view of the way in which the large tech companies are collecting huge amounts of data which is then processed by machine learning and AI to generate behavioural predictions which are in turn sold to advertisers for huge profits. The book covers a lot of ground and presents today’s reality from a different perspective. I was captivated by the description of an experiment in the year 2000 where engineers and researchers in Georgia Tech built the very first incarnation of an IoT enabled dwelling called the ‘Aware Home’ which they imagined as a human-home symbiosis.

‘There were three working assumptions: first, the scientists and engineers understood that the new data systems would produce a brand-new knowledge domain. Second, it was assumed that the rights to that new knowledge and the power to use it to improve one's life would belong exclusively to the people who live in the house. Third, the team assumed that for all of its digital wizardry, the Aware Home would take its place as a modern incarnation of the ancient conventions that understand "home" as the private sanctuary of those who dwell within its walls.’

What I find fascinating about the Aware Home is how different reality turned out less than twenty years later. The technology that powered this futuristic experiment has now become mainstream, but the vast amounts of data collected by the plethora of IoT devices does not belong to the people who live in today’s version of the Aware Home. We seem to take for granted that these internet-enabled services will be collecting our personal data and sharing it widely; sometimes in unexpected ways such as when an Alexa device in the US got its voice commands mixed up and emailed a recording of a private conversation between a couple to one of their friends. Despite these extreme examples we continue buying these products, hoping this won’t happen to us and accepting the collection of our personal data in exchange for services. We have agreed to these terms and conditions. It’s just that we do it without thinking.

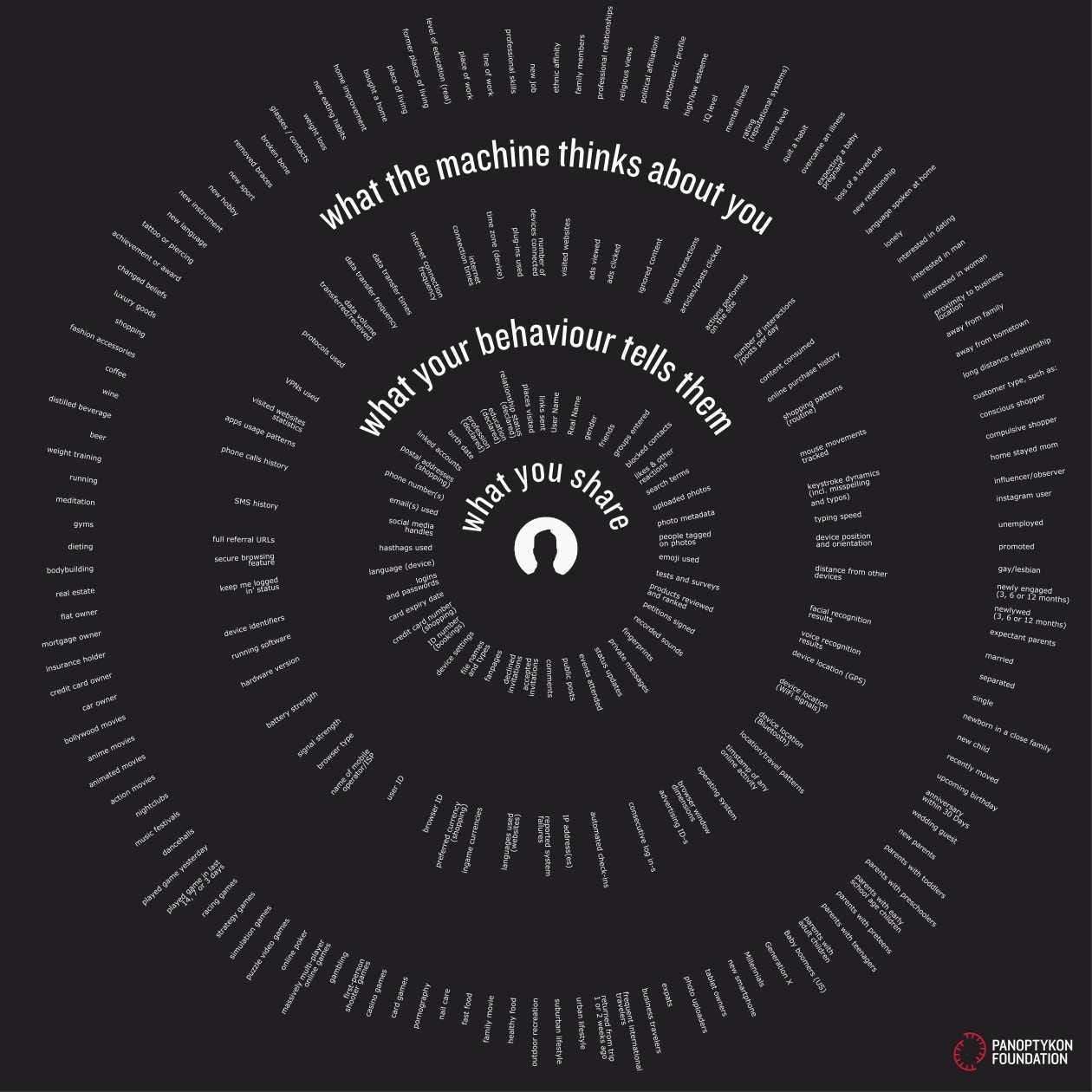

The legal framework of the internet is based on complex contracts that nobody reads. The Australian consumer advocacy group Choice hired an actor to read the 73,198 words of Amazon Kindle’s terms and conditions. It takes 9 hours! In a similar study, a group of researchers from the University of London determined that if a customer were to enter the Nest ecosystem of connected devices and apps they would need to review around 1000 contracts.

It is even argued that these contracts are carefully designed to nudge users to click without thinking, as an automated response to a carefully crafted stimulus. I find myself clicking ‘agree’ many times a day and consider it part and parcel of using the internet and technology products.

What is probably most ironic, is that with the introduction of GDPR in May last year there seems to have been an explosion in the number of agreements to click on every site. What is also true is the exponential increase in data breach complaints to European data protection regulators. Since the introduction of GDPR there have been over 95,000 complaints raised. This points to a growing dissatisfaction with the current state of affairs. Some of these complaints are being raised by UK social housing tenants or leaseholders who have an expectation that their landlords are protecting their data. This will become increasingly complex as the sector deploys IoT technology more extensively.

There is another interesting dimension to today’s reality which wasn’t envisaged in the year 2000 as part of the Aware Home’s experiments. As more intelligent devices are installed in the home and connected to the internet, the risk of an attack by hackers takes an entire new dimension. There is now the possibility to hijack internet-connected ‘things’ which interact with the physical world. All of a sudden the role of cybersecurity experts goes from preventing an attacker being able to encrypt someone’s spreadsheet or send phishing emails to trying to deal with attackers who are able to stop someone’s pacemaker, take control of a crane in a construction site, replace the video image and sound from an internet connected doorbell device or simply hijack the home’s thermostat and ask for a ransom.

The security of the connected home is becoming a national defence priority for many countries as highlighted by the Japanese government’s effort to hack IoT devices in the homes of ordinary members of the public to identify weaknesses and resolve them in advance of the 2020 Olympics.

We have managed to turn an idealistic experiment from the year 2000 into everyday reality but at the same time introduced new challenges regarding the ownership and protection of the behavioural data collected as part of the use of internet-enabled services. We are also becoming aware of the potential for cyber attacks on the physical world which may cause problems at an unprecedented scale. One thing is sure; the drive to build the connected home of the future will continue and is something which the housing sector must embrace.

What skills will the housing staff of the future need in order to advice and protect their residents? Will it be necessary to write alternative user guides such as these which focus on how to be aware of and minimise the inevitable digital surveillance being introduced into their homes with every new IoT device? Will it be necessary to have the skills to prevent attacks into internet connected home equipment or the building management system? In relation to the complex and extensive contracts, will landlords be able to provide clarity for residents to understand what happens to their data?

At HouseMark we have been thinking about these issues for a long time and in 2017 published ‘Transparency and Trust: A guide to data protection and privacy for social landlords and tenants’ which provides extensive guidance on how to safely collect, use and store personal data in the housing sector. Following the significant interest generated from this publication and to dive deeper into these issues we have established a Warning Advice and Response Point (WARP) for housing providers. WARPs have been going in the UK government for over 20 years and are groups of cybersecurity and data protection experts who work together to improve the security of their organisations through information sharing and collaboration. Chaired by Jeanette Alfano, Director of Technology and Transformation at Optivo and managed by HouseMark; the group started meeting in 2019 and collaborating on key topics such as the challenges of secure communications with partners such as local authorities or the police, how to mitigate security risks by achieving Cyber Essentials Plus certification and more immediate concerns such as how to respond to the letter from Fiona MacGregor to all CEOs of housing associations regarding the access to data stored in cloud facilities in Europe in the scenario of a no-deal Brexit.

We are aiming to keep the current group small with no more than 25 organisations but we are hoping to grow into regional WARPs over the next 6 to 12 months. With support from the National Cyber Security Centre and a number of security experts, we will be building the resilience of the sector to ensure that as we move to a more connected future with all its challenges, we have the tools and the skills to respond. If you are keen to join, please get in touch.

This article was published in the second edition of the DIN Bulletin