Data trust, dark patterns and the 2019 Women’s World Cup

Why customers should co-design digital services

As the people in the pub jumped up and down with joy at the great goal scored by England’s Ellen White in the women’s world cup semi-final game against the USA, I had this nagging feeling, learned over the last few games in the tournament, that we may be celebrating too early. As the cameras focused on the wild celebrations, a dramatic cut to an image of the referee communicating with a high-tech media centre almost 300 miles from the stadium gave it all away. An acronym unknown only a few months ago would take centre stage again: VAR.

We know what happened; the goal was disallowed because the England player was offside according to VAR using the virtual offside line rule. Here’s an extract from the FIFA website explaining this technology:

‘Virtual offside lines are superimposed on the broadcast image by computer software. Angle of view, lens distortion, field curvature and many other factors are considered when calculating the true position of these lines’.

There are a few interesting considerations from this single football incident, but to me the most fascinating one is the prevailing feeling that it was a fair decision. That even if we don’t like it, there is an objective way to determine the truth.

How did we get there? How can irrational fans accept that their wild celebrations were short-lived and ultimately pointless? There’s only one answer: Technology. Whereas in the past, referees would be turned into legends or hate figures because of their oversights or mistakes; today, thanks to technology, there is an objective truth created by the cold, impartial stare of computer vision and 3D modelling.

It is interesting to compare how technology can provide the objective truth in one domain but obscure it in another one. We are all familiar with the post-truth world created by mass scale disinformation enabled by technology. The examples from Cambridge Analytica and the recent debate around the inaccuracy and bias of facial recognition techniques used by police forces in the UK demonstrate this trend.

How do we benefit from the potential of disruptive technology without eroding the trust of our residents? This is one of the key questions for digital leaders in housing responsible for building an effective customer experience. We know that in housing, the trust between residents and landlords is weak and this has been emphasised by the Green Paper for Social Housing and its focus on consumer metrics aimed to provide a measurable improvement in customer experience. How does this work when the customer experience is shifting to digital and the most disruptive tools and approaches are suffering from a major public backlash (techlash)?

Some positive solutions to this challenge are emerging from the practice of design thinking which combines some of the skills and tools used by designers with a relentless focus on looking at issues from the perspective of the user. The UK government is a global centre of excellence in this discipline with a strong practice across departments, kicked off by GDS. The outcome of implementing these techniques in the development of digital solutions is a better customer experience because users have been involved from the start and services have been designed around their needs. This is essential to meet the demands of the green paper around resident involvement in the co-creation of services, but it is also good business sense as poorly designed digital services end up generating more back-office demand and decreasing customer satisfaction and trust. A growing number of organisations have already realised the key role that good user-centred digital service plays on building trust and have embedded it in their design manuals guiding all their activities. Here are some examples from the NHS, Coop and a template for charities

At HouseMark we are seeing a growing interest in design thinking approaches to digital services. Our digital transformation programme is focused on sharing skills and lessons from organisations inside and outside the sector who have transformed their customer experience. In partnership with BT, we take participants in the programme through an intensive 2-day hothouse at Adastral Park where design thinking and user centred design techniques are put to the test. We expect a significant improvement in digital services in housing over the next few years as the need to deliver true co-designed services with residents gains momentum through the green paper imperative and colleagues in the sector embed user centred design into everything they do.

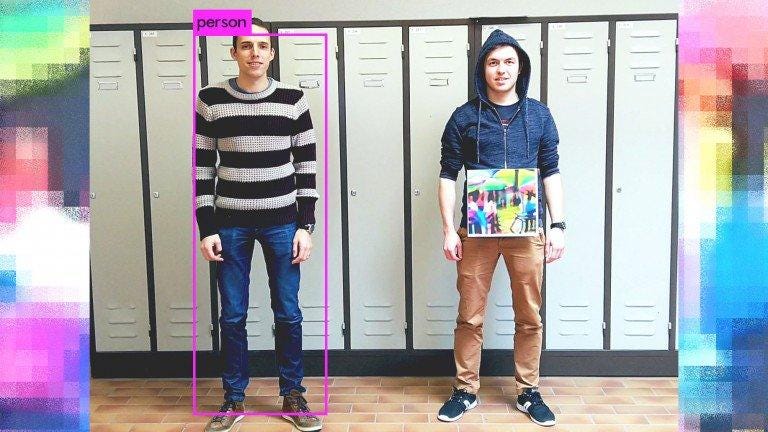

One of the foundations for building truly user centred digital services is to carry out effective and regular user testing. How can you build a service from the perspective of the user if real people are not involved in testing them and providing feedback? User testing is not some vague one-off consultation effort but an embedded practice which must form part of every transformation team. High quality user testing comes with some important challenges which are being highlighted recently in the debate around dark patterns and efforts to legislate them in the US senate. A dark pattern is a digital user interface which has been designed specifically to trick users into doing things. Examples of this type of design are everywhere on the internet, from the service that is easy to get into but almost impossible to escape; to the application where additional items are added to the shopping basket via imperceptible opt out options; to websites that ask for email or social media permissions for one purpose but then use the data to send spam emails.

User testing will prove that a specific service meets the users’ needs and delivers a great customer experience, but it can also prove that the desired user behaviour can be engineered by using things like dark patterns. Someone’s design flair is someone else’s dark pattern. Digital leaders in housing must be aware of these emerging challenges and be vigilant not to appear in name and shame lists such as the #darkpatterns twitter hashtag.

So, the next time you sit at a football ground wondering whether to celebrate or not while the person in black with the whistle waits for the decision of a computer to determine the truth of what really happened; don’t feel despondent. At least in that stadium there is trust in technology supporting the truth. When you go back to work on Monday building disruptive digital services you will be negotiating a rather more nuanced environment and wondering how to make sure tech is on your side of the offside line.

This article was published in the third edition of the DIN Bulletin