A mutant algorithm ruined my life

Taking tests in the age of AI

I clearly remember May 2018 and the constant fear of an impending data protection Armageddon. Working long hours to ensure all suppliers had signed GDPR compliant contracts, reviewing all data stored in multiple systems, reviewing privacy policies and in general feeling like the Y2K bug all over again. I remember organising events for HouseMark members with expert lawyers and attending Boards to talk about the areas to look out for (like the potential for an increased number of SARs). One of the things from that period that I remember the most was trying to understand the more obscure items in the legislation and there was none more perplexing than Article 22 also known as the ‘right to explanation of automated individual decision-making including profiling’. In principle, the idea is fairly simple: data subjects should be able to understand how an algorithm arrived at a decision which affects them but in practice, this turned out to be a very complex debate triggering the launch of an inquiry in the House of Commons, the creation of a new Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation and numerous debates about what this means for people. I remember trying to come up with good examples to illustrate this specific point and always feeling it was just a theoretical concept or an academic argument.

Two years later, a global pandemic would provide a perfect and tragic example which will forever define what it means for an unexplainable algorithm to make a decision with a major impact on people's lives.

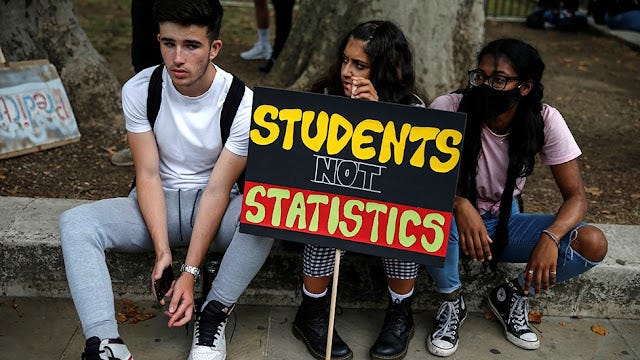

Everyone knows the story. The Coronavirus would force schools to shut down in March 2020 and a decision was made early by the government that A-levels and GCSE exams would not be taken, and an alternative method of awarding grades would be developed by Ofqual. A few months later, when the results came out and caused a significant number of students to have their expected grades downgraded, the inquest started immediately, and the culprit identified. It was an algorithm that had taken a number of rules, crunched them, and provided a result with massive real-world consequences for a whole generation of students. The fallout has been epic, and the knock-on effects will take years to unravel.

There are significant lessons for Housing organisations as the sector makes more use of data and algorithms to support decisions.

Colleagues working with data should consider the impact of working with small cohorts which in the case of the exams algorithm ended up benefitting private schools over state schools with larger classes and a wider distribution of grades.

Strategy and policy colleagues should think carefully about how implementing some policy objectives may have unintended consequences. In the case of the exams algorithm, the policy objective of Ofqual is to ensure exams are fair and even with year-on-year comparability regardless of any changes in curriculum or grades methodology. Having to implement this policy in a year in which exams were cancelled due to the pandemic triggered the creation of a set of complex rules which disregarded the assessment of teachers and ended up causing inexplicable and unfair results.

Data models should be put through a ‘common sense’ test to challenge the results which don’t work in changing circumstances. In the case of the A-levels algorithm, the award of ‘U’ grades is a Good example. In a normal exam year, ‘U’ grades are mostly awarded to students who don’t take the exam. This is frequently due to a misfortune such as a panic attack on the day, a bereavement or an accident. In 2020, ‘U’ grades were distributed by the algorithm based on its defined rules but when you apply a ’common sense’ test to this, it looks pretty odd for an algorithm to statistically distribute unpredictable events. You cannot fail to turn up to a non-existent exam!

Organisations should comply with a recognised data ethics framework in their advanced analytics projects.

Leaders should be aware of the impact of algorithmic decision-making and try to work in the open when developing these approaches. Ofqual, to their credit, consulted heavily on their algorithm but still several mistakes were made which ended up contributing to the fiasco

The chair of Ofqual, Roger Taylor, said to the House of Commons Education Committee that it was a "fundamental mistake" to believe that it “would ever be acceptable” to use an algorithm to award grades for this year’s A-level. This is a serious blow to public confidence in algorithmic decision-making and particularly ironic coming from Taylor who also chairs the Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation which was created in those early days of GDPR to provide clarity and trust in algorithms.

The importance of data-based decisions, which has been highlighted during the pandemic, will continue to grow, but Housing colleagues must learn from this cautionary tale and ensure the necessary controls are in place and data can be trusted. Organisations will have to work harder than ever to regain trust as the mutant algorithm could strike again.